Best Practices for Qualitative Coding

Last updated on 2025-04-16 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 60 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What is the difference between inductive and deductive coding?

- How can I set up and apply a flexible code tree in QualCoder?

- How can I code text and view coded text in QualCoder?

Objectives

- Distinguish between inductive and deductive approaches to coding

- Develop deductive codes relevant to project objectives

- Code text and view coded text in QualCoder

Getting Started with Coding: Why We Code Qualitative Data

Many qualitative researchers spend much of their analytic effort on coding data, i.e. assigning labels to excerpts in the data. That is also what we will focus on today. But before doing so, it is still worthwhile to focus on why we code in the first place.

Coding is a form of abstraction: we make sense of large (sometimes overwhelming) amounts of qualitative data – somtimes referred to as “unstructured data” and generate some structure by coding it. This abstraction is not cost free: by forcing codes onto your data, you may lose some nuance and specificity. Some qualitative traditions will therefore encourage you to only start coding once you are deeply familiar with your data. Most traditions encourage an ongoing back-and-forth between data and codes to make sure data and codes match.

Moreover, the role of codes varies strongly between qualitative research traditions. In some traditions, codes are principally a background tool, used to organize materials for later writing. That is the case, for example, for most ethnographic writing, as well as for many historically oriented approaches such as comparative historical analysis (as used in sociology and political science) or process tracing (as used in political science and administrative sciences). You will rarely find a mention of codes, coding schemas, or a codebook in published work using these methods, and not all of its practitioners may apply codes to data at all.

In other approaches, such as thematic analysis or discourse analysis, codes are a key analytic outcome. Here, codes don’t just organize the data but are used a tool to give it meaning. In publications using these methods, the codes and their development are typically made explicit and often form the core of the methods section. The tools we provide in this workshop can help you with either type of analysis, but as you develop your coding schema, you want to be clear where you situate yourself methodologically.

Beginning qualitative researchers often want to jump right into analyzing data once documents are added to a project, but taking the time to develop a coding protocol first can save time and improve the transparency and quality of research.

The first step is typically to choose a coding philosophy, that is, to decide how and why code labels will be chosen and applied. Coding philosophies range along a spectrum from inductive to deductive approaches.

Deductive and Inductive Reasoning

Deductive reasoning begins from assumptions and hypotheses. It seeks to determine, using logic or data, whether the hypotheses can be shown to be false (or true).

Experimental methods in many disciples follow this pattern. First, a hypothesis or prediction about the effect of some cause is developed based on past research and observation. An experiment is conducted to isolate that specific potential cause, and conclusions are drawn based on the presence (or lack) of difference made by the difference.

A medicine trial is a classic example of a deductive approach. Scientists predict a treatment will help people in a specific way (for example, by reducing the length of an infection). They recruit participants (patients with the infection) who are randomly assigned so that some receive the medicine and others receive a placebo with no medicine. If the length of the infection is statistically shorter in the patients who received the medicine, that is taken as evidence that the medicine likely produced the desired result.

Deductive reasoning relies on minimizing exposure to outside variables that might affect the outcome of interest, or otherwise statistically adjusting for potential confounding factors.

Inductive reasoning, by contrast, seeks to draw more naturalistic conclusions by making close observations while recognizing personal biases and limits to observation. Inductive qualitative research draws on patterns observed in data to make predictions, generalizations, or analogies about more general patterns. Put differently, deductive research is typically explanatory in nature, while inductive research is exploratory.

Inductive social research often draws on critical or constructivist perspectives that emphasize how individuals and groups describe their own experience.

Taken in a longer scope, science can only develop through the complementary use of induction and deduction, sometimes visualized as a circular cycle. Observation is used to develop hypotheses, which are tested deductively through more observation. If hypotheses are not fully confirmed, inductive reasoning is used to develop revised or alternative hypotheses.

Even though deductive and inductive reasoning are both part of nearly every study in some way, how qualitative data is coded depends on the general purpose of the study. Exploratory studies tend to adopt an inductive method, while explanatory studies use more deductive approaches to code development.

Inductive coding

In 1967, US sociologists Glaser and Strauss formalized grounded theory, one method for conducting structured qualitative research without presupposing a hypothesis or theory. They recognized that how people experience the world can be at least as important as traditional measures (i.e., personal income or gross domestic product).

In grounded theory and other inductive coding methods, qualitative data like interview transcripts are read carefully and initial codes are applied that match the language and interpretation proposed by study participants themselves as closely as possible.

Often, researchers label codes in this open coding phase by using their judgment and experience to discern underlying themes in the experiences expressed across interviews.

In our scenario, the goal of this analysis is to prepare for

collecting and analyzing new data related to social media privacy and

confidentiality. BSR_05 is an interview with a PhD student

studying political communication.

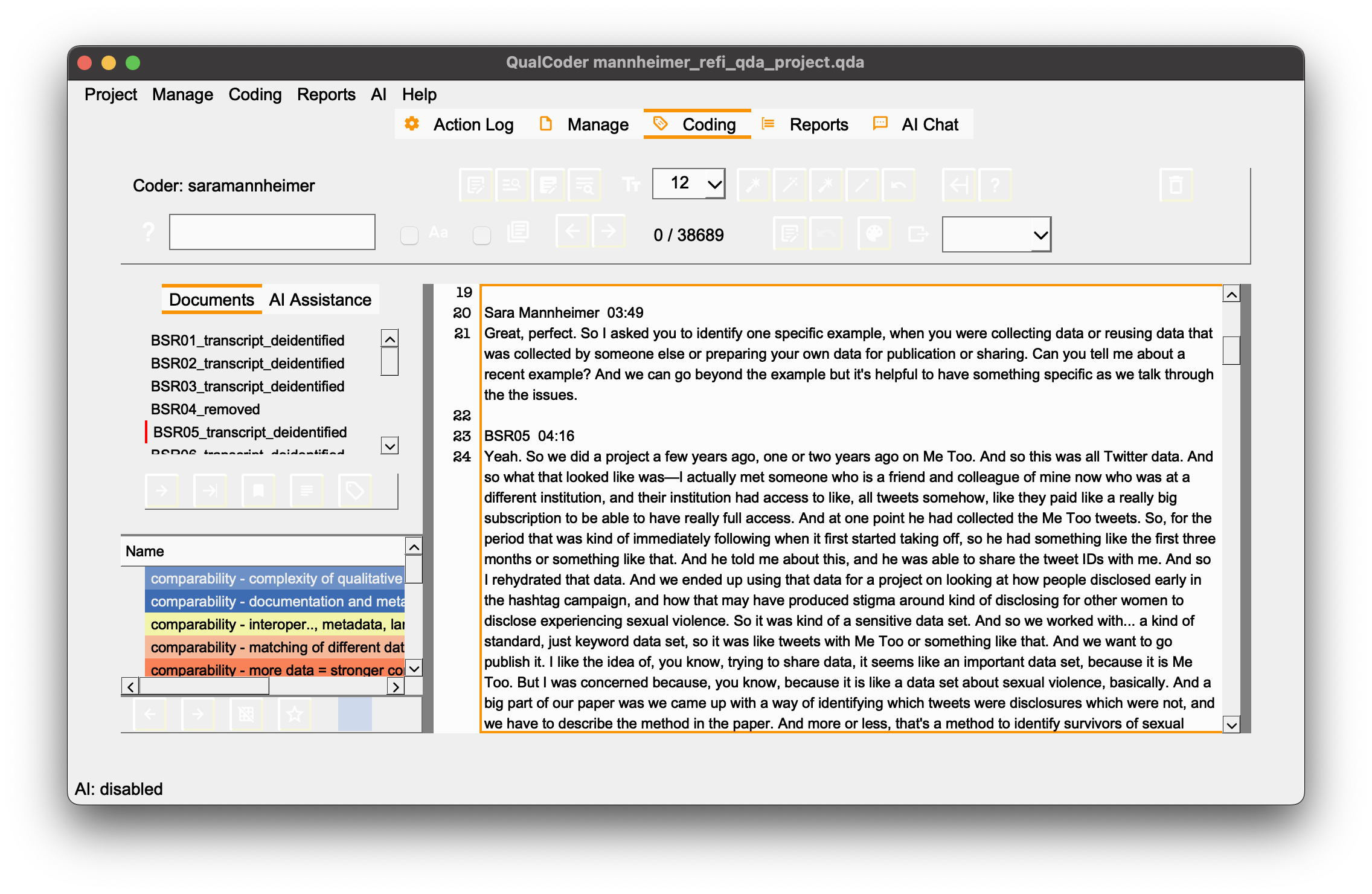

Open the Coding tab to Code text in

QualCoder and click on BSR05_transcript_deidentified in the

Documents list to open it for coding on the right.

Sara Mannheimer is the interviewer and BSR05

replaces the name of the student for privacy protection.

Codes (labels) are applied to text segments that reflect a particular concept, theme or idea. Before applying a code, it must be created in the Codes list or the Code organizer.

Codes can be nested within one or more levels of categories, which can distinguish coding processes, larger themes, or code status (such as draft). Importantly, and different from many other QDAS, QualCoder does not allow you to code directly to a category or to create subcodes of a code. They serve different purposes.

Open coding

We will start by creating open (inductive) codes. Return to the text

coding screen (Coding - Code text). Select

BSR05 again. Scrolling 3 minutes and 49 seconds into the

interview, we learn this person was using a large dataset of Twitter

posts from the #MeToo movement with some significant privacy risks, for

example:

And a big part of our paper was we came up with a way of identifying which tweets were disclosures which were not, and we have to describe the method in the paper. And more or less, that’s a method to identify survivors of sexual violence in our in our data set.

The next challenge is flexible and can be done as a class or as a think-pair-share, where individuals spend 1-2 minutes brainstorming alone, then share with a partner and discuss, then with the class.

Creating open codes

Discuss as a class what kinds of labels you, as a social media privacy researcher, might apply to part or all of the excerpt above.

Open codes can range from very specific to more general, but theoretically fruitful codes are often somewhere in the middle - general enough to apply in multiple situations but specific enough those excerpts have something more in common.

There are multiple words or phrases that might capture some of this excerpt’s relevance for our research. QualCoder allows applying multiple codes to identical or overlapping excerpts. Doing so makes it easier to consider overlapping concepts, like “privacy” and “identity protection,” as well as other aspects of the context, such as “sexual violence” or “crime victimization”.

Codes must be created before they can be applied.

First, right-click in the code list and

Add a new category called open coding for our

codes.

Next, right-click the category and

Add a new code to category, naming it after a theme or

concept you identified (i.e., privacy).

Highlight the relevant text chunk at right with your mouse (“And a

big part… in our data set”) then click your new code. If it worked

correctly, you will see a count of 1 next to your code and

once you click somewhere else, the text will be highlighted in the

code’s color.

How many codes?

A single sentence often relates to multiple topics, so it’s common to apply more than one code to a single chunk of text or apply codes to overlapping text chunks. The next part of the workshop will discuss some of the reasons overlapping codes can be valuable.

To apply multiple codes to the same (or overlapping) text, repeat the

coding process with another code. QualCoder will display the overlap as

underlined text. Clicking on the underlined text will change to

one of the highlight colors, which can be cycled by pressing the

o key or clicking the code of interest.

How much to code?

Decisions about how large of excerpts to use are challenging but important. Highlights generally should be only long enough to provide context and understand meaning. Some researchers always code full sentences or even paragraphs, while others make decisions case by case.

I might create codes for both “privacy” and “identity protection” but later realize they overlap so much conceptually they don’t need to be separated.

To merge two codes, load them in the Code organizer,

right-click the code you want to replace, and choose

Merge code into code then Apply. After

merging, any text coded to one or both original code will have the name

of the “into” tag and the other will be removed.

Unmarking coded text

Beyond merging codes, sometimes you may accidentally mark an excerpt

and want to remove one or more codes entirely. To remove a code,

right-click and choose Unmark. Trying to unmark text where

multiple codes have been applied will trigger a dialog box asking which

codes to unmark.

Unmark can also be used to adjust the start and end point of an excerpt. There are built-in tools available with right-click but they rely on counting the number of characters to move the endpoint so it may be easier to unmark and re-code instead.

In vivo coding

An alternative approach to inductive coding, in vivo coding, tries to further reduce researcher bias effects by creating initial code labels only from the language used in the interviews themselves.

Let’s look at a passage slightly earlier in the paragraph we’ve been

working with in BSR_05.

And we ended up using that data for a project on looking at how people disclosed early in the hashtag campaign, and how that may have produced stigma around kind of disclosing for other women to disclose experiencing sexual violence. So it was kind of a sensitive data set.

The person being interviewed used a number of words and phrases that may be relevant to data privacy protection in these sentences including disclosed, stigma, disclosing, disclose, experience, sexual violence, and sensitive data. Rather than categorizing themes at this stage, in vivo coding retains language used by the participants.

After creating another category for in vivo codes,

highlight “disclosed”, right-click, and choose

in vivo code. This will add the exact word or phrase

highlighted as a code (if it does not exist). Do the same for other

language related to disclosure or sexual violence in the short

passage.

Managing in vivo codes

Before using in vivo code in QualCoder, it is best to

ensure all existing codes, such as themes, are added to categories. This

prevents mixing up in vivo codes with other codes.

When you have finished in vivo coding, codes can be moved to the

in vivo category by dragging them onto the category name or

right-clicking and selecting move code to.

At this point, you may also want to consolidate in vivo codes of the

same root word, such as disclose and

disclosure. Instructions for merging can be found under

How much to code above.

Be careful, however. If you move codes before coding is complete and later code the same word or phrase, it will be created as a separate code.

In vivo codes can be analyzed individually to understand specific language people use or aggregated into themes during the axial coding process.

Deductive coding

Deductive codes are applied much the same way as open codes, but development of a coding tree takes place earlier, ideally before data collection, because tags and themes reflect theories and hypotheses the study is designed to test.

Code deductively

Our research team has adapted 3 key themes from Sarikakis and Winter’s 2017 review of social media user’s consciousness of data privacy: 1. Autonomy: users desire control over when and to whom their data is disclosed 2. Compromise: users recognize privacy’s importance but also circumvent protections when seeking information 3. Stake: concern derives from being personally affected by privacy or sharing

Create the 3 themes above as codes within a new category called

deductive. Add descriptions based on the background given

above by right-clicking and choosing View or edit memo. You

can use memos to clarify exactly what a code means, to note questions

about whether something should be changed, or any other purpose. Memos

provide flexibility within a project to fill in gaps between formal

parts of the project.

In BSR_02, read and highlight the text block quoted

below (from the section starting at 1:44).

I’ve done some work on on Twitter on how like social people who are users of Twitter, I’ve done, did a project on on people who have been harassed on Twitter and the subject of kind of coordinated harassment campaigns, and how kind of their experiences.

In groups of 2-3 people, discuss whether each theme is relevant and why, then apply relevant codes to the excerpt.

Don’t focus on finding key words or synonyms in deciding whether to apply a code. Look for sections that suggest a relationship to themes of interest.

Autonomy might apply depending on whether the harassment people experienced on Twitter included doxxing or otherwise involved personal information. Without access to the original interviewee, it’s probably not reliable enough to use in drawing conclusions.

Compromise does not seem relevant here, as the presence of online harassment suggests the advantage of stricter protections, if anything.

Stake clearly applies. The Twitter users are described as experiencing coordinated harassment campaigns on Twitter, meaning not only is the platform used to harass, but to encourage others to do the same.

Like inductive and deductive reasoning, the separation between inductive and deductive coding is rarely complete. As a researcher, how closely you adhere to a single reasoning or coding model will likely depend on personal research questions and values, as well as norms in the fields where the research will be shared.

Axial coding

Most qualitative projects require more than one round of coding for a few reasons:

- The first documents rarely highlight every relevant theme. Themes and language important in later interviews may still be reflected in early interviews but less obvious before the theme was brought to the researcher’s attention. Revisiting early interviews supports consistent code application.

- Multiple coders may use tags in slightly different ways, which eventually need to be adjusted to a consistent scheme.

- Key relationships between codes may only become obvious once initial codes are considered, leading to consolidation or the development of new tags as researchers become more familiar with the documents and themes.

- When coding in vivo, people may use language differently and multiple phrases may represent a single idea.

Axial coding primarily addresses numbers 3 and 4, as it is involves relating or further breaking down primary themes or codes.

For example, the passage in BSR_05 coded to

in vivo - disclosure concerned self-disclosure of personal

information during the #MeToo movement with the hope of reducing stigma

and producing a positive outcome. But Twitter users in

BSR_02 may have been subject to disclosure of personal

information without consent. Axial coding might involve distinguishing

disclosure based on whether it was voluntary or self-directed.

Axial coding takes many other forms, depending on the research topic and methods. Deductive research may revise and further specify existing theory based on new data in their study. In vivo codes or open codes that seemed distinct may turn out to be conceptually indistinguishable. Participants may be provided summaries of initial findings and asked if they reflect their personal experience. In all cases, axial coding is a tool to clarify analysis and theory.

Qualitative studies typically have one or more rounds of initial coding, followed by any amount of axial coding necessary to represent key concepts intelligibly to both researchers and study participants.

Importing QDPX projects

The data collection we found includes a QDPX project

containing not only all the interview transcripts, but also the coding

scheme and coded text used by the original research team.

To import, select

Project - Import - REFI-QDA Project Import (not codebook

import). Choose a name and location to store the project then navigate

to the QDPX file and complete the import.

Importing a project creates a new QualCoder project. Since your

existing work is auto-saved, you can switch between the two later using

Project - Open Recent Project.

Before going further, use Manage - Manage files to check

what files are in the new project.

Coding reports

Coding view (Coding - Code text) is optimized for

reading through transcripts or documents and applying a variety of

codes, but it can be difficult to get a sense of what all is matches a

particular code in your document corpus using coding view.

The Coding report allows you to view every text passage

coded to a single code (or set of codes), optionally restricted to

specific source documents. This can be a great help to axial coding

because you can look at one or more related codes more closely to see if

they should be merged, split, relabeled, or left as-is.

Create a report using Reports - Coding report. Nothing

should display in the right window, but sources will be listed in the

top-left and codes in the bottom-left.

Select only the Big Social Research interviews by right-clicking in

the sources, choosing Select files like and entering

BSR in the dialogue (it must be all-caps).

Let’s focus on privacy harms using the codes from the original study

team. Find and click the

privacy - considering potential harms category. When you

select a category, any codes linked below it in the coding tree will

also be included. Finally press the play button

(right-facing triangle) to run the report.

The report shows all three text chunks coded to any of the selected privacy codes in the BSR interviews, with information on the code, file, and coder in a highlighted row above the excerpt.

Categories with codes

Other major QDAS, unlike QualCoder, allows coding directly to categories. This project was originally created in NVivo and had text coded to both codes and categories. When importing a QDPX project, QualCoder creates codes with identical names when it encounters a category with codes.

Privacy - considering potential harms is an example of

this behavior, where a code duplicating the category was automatically

created.

Axial coding with reports

Read through the three results in the above report. Each one currently has a different code applied. Based on the text and names, discuss with the group whether you think they represent similar enough concepts their codes should be combined if these were the only interviews being considered.

There is no authoritative right or wrong answer here. Whether to combine or split codes depends on the research questions, methods, and subjectivities, as well as on what participants tell you. The most important guide is to ensure that you are treating your research participants in a way that is faithful to their own experience, as you understand it.

We won’t make any changes at this time, but if you did want to merge

two codes, you would use the Code organizer or

Code text screen, right-click one, and select

Merge code into code. Now both will be a single code by the

into name, which you can rename if needed.

QualCoder’s coding tools (specifically Code text,

Code organizer and Coding report) comprise the

core suite for the coding process itself. In the next section, we will

build on that foundation and explore qualitative and mixed methods

analysis methods that can be used in QualCoder.

- Qualitative code protocols are developed based on research goals and philosophies

- Inductive research focuses on discovering or exploring themes and often uses open or in vivo coding

- Deductive research focuses on testing hypotheses and typically applies a predefined coding scheme based on theory

- In QualCoder, codes are labels applied to highlighted excerpts of text